www.burywatermeadowsgroup.org.uk

Bury Water Meadows Group came together in 2013 to help safeguard the ‘Leg of Mutton’ – a large green open space that is part of the character of the historic market town of Bury St Edmunds.

The Group comprises concerned residents, local associations and groups, and members of the Suffolk Wildlife Trust.

The Rivers Lark and Linnet (both rare chalk streams), and the land around them, have been essential parts of Bury St Edmunds for many centuries. These precious green spaces and rural landscapes are very important in contributing to the town’s historic setting and identity. To retain the character of the town, and preserve its heritage, they should be considered as key elements of the town for future generations.

In 2019 the Bury Water Meadows Group became a Charitable Incorporated Organisation (registered charity, number 1185321) with the following objects:

To conserve, preserve and improve the Rivers Lark and Linnet in Bury St Edmunds and adjacent areas for the benefit the public, in particular but not exclusively by:

1. Improving access and encouraging the appropriate use of the Rivers and their environs by members of the public.

2. Educating the public about the Rivers and their environs

3. Facilitating community involvement in the conservation of the River Lark and Linnet, Bury St Edmunds’s water meadows and critical adjacent areas such as Leg of Mutton

4. Improving the biodiversity of the Lark and the Linnet

5. Working in partnership with like-minded organisations

Bury Water Meadows Group came together in 2013 to help safeguard the ‘Leg of Mutton’ – a large green open space that is part of the character of the historic market town of Bury St Edmunds.

The Group comprises concerned residents, local associations and groups, and members of the Suffolk Wildlife Trust.

The Rivers Lark and Linnet (both rare chalk streams), and the land around them, have been essential parts of Bury St Edmunds for many centuries. These precious green spaces and rural landscapes are very important in contributing to the town’s historic setting and identity. To retain the character of the town, and preserve its heritage, they should be considered as key elements of the town for future generations.

In 2019 the Bury Water Meadows Group became a Charitable Incorporated Organisation (registered charity, number 1185321) with the following objects:

To conserve, preserve and improve the Rivers Lark and Linnet in Bury St Edmunds and adjacent areas for the benefit the public, in particular but not exclusively by:

1. Improving access and encouraging the appropriate use of the Rivers and their environs by members of the public.

2. Educating the public about the Rivers and their environs

3. Facilitating community involvement in the conservation of the River Lark and Linnet, Bury St Edmunds’s water meadows and critical adjacent areas such as Leg of Mutton

4. Improving the biodiversity of the Lark and the Linnet

5. Working in partnership with like-minded organisations

The Lark and the Linnet

Bury’s two rivers, the Lark and the Linnet, are chalk streams that are fed from springs in the underlying (chalk) aquifer. The Linnet, 10km long to the Lark’s 50km, rises near Chedburgh, to the south west of Bury St Edmunds. The Lark rises at the 100m AOD (above Ordnance Datum) contour south of Bury, and a number of tributaries contribute to its source. It flows over the boulder clay that overlies the chalk and continues in a south east to north west direction until the chalk becomes exposed near Lackford, 10km downstream of Bury. A major tributary, the Cavenham Stream, joins the Lark 2km downstream of Lackford.

As the river flows over the chalk outcrop, the underlying aquifer provides a significant contribution to the flow. Between Mildenhall and Isleham the River Kennett and the Lea Brook join the Lark from the south. Over the final 14.5 km stretch to the junction with the Ely Ouse the low lying Fens are underlain by impervious Gault clay and at the confluence by Kimmeridge, Ampthill and Oxford clays.

Global and regional context

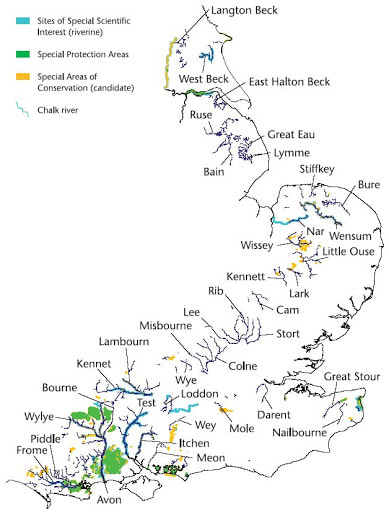

Throughout the world chalk streams are rare, and England, with an estimated 224, has 85% of them (O’Neill and Hughes, 2014). They follow the band of chalk that sweeps diagonally north east from the south coast under the Wash to Yorkshire. The Lark and Linnet are the two most important chalk watercourses in the southern Brecks, mirrored in the northern side of the area by the Rivers Gadder, Nar and Wissey (which, like the Lark, flow into the Ouse).

Bury’s two rivers, the Lark and the Linnet, are chalk streams that are fed from springs in the underlying (chalk) aquifer. The Linnet, 10km long to the Lark’s 50km, rises near Chedburgh, to the south west of Bury St Edmunds. The Lark rises at the 100m AOD (above Ordnance Datum) contour south of Bury, and a number of tributaries contribute to its source. It flows over the boulder clay that overlies the chalk and continues in a south east to north west direction until the chalk becomes exposed near Lackford, 10km downstream of Bury. A major tributary, the Cavenham Stream, joins the Lark 2km downstream of Lackford.

As the river flows over the chalk outcrop, the underlying aquifer provides a significant contribution to the flow. Between Mildenhall and Isleham the River Kennett and the Lea Brook join the Lark from the south. Over the final 14.5 km stretch to the junction with the Ely Ouse the low lying Fens are underlain by impervious Gault clay and at the confluence by Kimmeridge, Ampthill and Oxford clays.

Global and regional context

Throughout the world chalk streams are rare, and England, with an estimated 224, has 85% of them (O’Neill and Hughes, 2014). They follow the band of chalk that sweeps diagonally north east from the south coast under the Wash to Yorkshire. The Lark and Linnet are the two most important chalk watercourses in the southern Brecks, mirrored in the northern side of the area by the Rivers Gadder, Nar and Wissey (which, like the Lark, flow into the Ouse).

Flow and seasonality

Under natural conditions, the slow release of water from the aquifer produces a relatively stable river flow in chalk streams, with a characteristic annual cycle and constant temperature of around 11C, meaning they rarely freeze. After the onset of autumn/winter rains, the flow tends to increase in December, associated with a rainfall-induced rise in shallower sections of the aquifer, and continues to increase until March or April.

During winter, flow from springs at the perennial head increases in strength, whilst springs along the ephemeral ‘winterbourne’ section reactivate after lying dormant through the summer months. Flows then decline steadily through the summer and autumn until the shallow aquifer is again bolstered in the winter by percolating autumnal rainfall. The Linnet has an ephemeral section in the West of the town that is usually dry in the summer despite there being water in the channel both up and downstream. It is not clear from historic record whether this has always been the case.

Peak flows after heavy rain are relatively small compared to ‘flashier’ river types, and are sustained for longer periods by the high spring-fed component. In their pristine state spring-fed channels have been found to equal or exceed bank-full flows for around 30% of the time (Whiting and Starn, 1995), which produces sustained waterlogging in riparian areas, a characteristic of classic chalk river floodplains. This is not the case in Bury today, although the Linnet floodplain is waterlogged for a few days most years in recent times. 200 to 300 year-old native black poplar trees (Populus nigra var. betulifolia) on No Mans Meadow (south of the abbey) indicate the area was boggy in the past.

Under natural conditions, the slow release of water from the aquifer produces a relatively stable river flow in chalk streams, with a characteristic annual cycle and constant temperature of around 11C, meaning they rarely freeze. After the onset of autumn/winter rains, the flow tends to increase in December, associated with a rainfall-induced rise in shallower sections of the aquifer, and continues to increase until March or April.

During winter, flow from springs at the perennial head increases in strength, whilst springs along the ephemeral ‘winterbourne’ section reactivate after lying dormant through the summer months. Flows then decline steadily through the summer and autumn until the shallow aquifer is again bolstered in the winter by percolating autumnal rainfall. The Linnet has an ephemeral section in the West of the town that is usually dry in the summer despite there being water in the channel both up and downstream. It is not clear from historic record whether this has always been the case.

Peak flows after heavy rain are relatively small compared to ‘flashier’ river types, and are sustained for longer periods by the high spring-fed component. In their pristine state spring-fed channels have been found to equal or exceed bank-full flows for around 30% of the time (Whiting and Starn, 1995), which produces sustained waterlogging in riparian areas, a characteristic of classic chalk river floodplains. This is not the case in Bury today, although the Linnet floodplain is waterlogged for a few days most years in recent times. 200 to 300 year-old native black poplar trees (Populus nigra var. betulifolia) on No Mans Meadow (south of the abbey) indicate the area was boggy in the past.

Looking north towards the cathedral over the Lark (foreground) and flooded No Mans Meadow in December 2020

Libby Ranzetta, December 2020